D.H. Lawrence Ranch

Directions

Physical Address: 506 D.H. Lawrence Ranch Rd, Taos, NM

From US-64 West Paseo Del Pueblo Norte, continue straight onto NM-522 North for approximately 10 miles, take a slight right onto Lawrence Ranch Rd and continue for 4.7 miles. The Ranch will be on the right.

Google Maps may offer a route via NM 150 and Galina Road. PLEASE DO NOT TAKE THIS ROUTE. THE ROAD IS IMPASSABLE. Use the above route via NM-522.

Opening Hours

Effective March 12, 2022, the DHL Ranch will be open to visitors on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 9:30 a.m. – 3:30 p.m.

If you have any questions regarding your visit to the D.H. Lawrence Ranch, please call The D.H. Lawrence Ranch office at (575) 776-2245.

Cabins are not available to rent at this time.

Lawrence and the Ranch

D. H. Lawrence, the author of literary classics such as Women in Love and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and his wife Frieda first came to New Mexico in September 1922 at the invitation of Mabel Dodge Luhan, a New York socialite and arts patron who lived in Taos. The trip was pivotal for Lawrence. While the English-born writer only spent a total of eleven months during his three visits to New Mexico, the state made a notable impression on him. He wrote:

I think New Mexico was the greatest experience I ever had from the outside world. It certainly changed me forever.

In March 1924, Lawrence and his wife, accompanied by Dorothy Brett, an English painter and admirer of the author, returned a second time to Taos. On this visit, Mabel Dodge Luhan gave Frieda a ranch she owned located 20 miles northwest of Taos on Lobo Mountain. The 160 acres was known as the Kiowa Ranch because the Kiowa Indians had used a trail which ran through the property when they traveled south to raid Indian pueblos along the Rio Grande.

Situated at 8,600 feet above sea level, the ranch was first established in the late 1880s by a homesteader, John Craig. In 1893 he sold the ranch to Mary and William L. McClure who raised angora goats on the property. Luhan purchased the ranch from the McClures in May 1920.

Lawrence and Frieda along with Lady Brett, who was the Earl of Esher’s daughter, moved to the ranch in May 1924 and spent five months there. During the summer, Lawrence completed his short novel “St.Mawr” in which he celebrates the special quality and landscape of the Kiowa Ranch. Lawrence also wrote his biblical drama, “David” and parts of “The Plumed Serpent” during his last visit to the ranch (April-Sept. 1925). New Mexico also figures prominently in other essays and stories such as “The Woman Who Rode Away.”

After Lawrence died near Vence, France in 1930, Frieda returned to New Mexico to live. In 1934, she had Lawrence’s body exhumed, cremated and his ashes brought to the ranch to be housed in a small memorial chapel. In 1955, eight months prior to her death, Frieda gave the Kiowa Ranch to the University of New Mexico. She stipulated that the ranch be used for educational, cultural and recreational purposes and that the Lawrence memorial be open to the public. Since then the ranch has been known as the D. H. Lawrence Ranch.

The Homesteader’s Cabin

On May 5, 1924, when D. H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda moved to the Kiowa Ranch, two dwellings and a small barn existed on the property. Of the two, Lawrence and Frieda chose the Homesteader’s Cabin, the largest house, as their mountain home. English painter and Lawrence disciple, Dorothy Brett lived in the smallest cabin.

The cabin features three rooms — a kitchen/dining area, a large middle room and a bedroom — and was probably built sometime during the later part of the 19th century by John Craig, who homesteaded the land in the 1880s. Ponderosa pines cut from the property were used to build this and the other cabins. An adobe plaster, a mixture of mud, straw and water, can be seen between the pine logs. The west wall of the Homesteader’s Cabin features a striking picture of a buffalo painted in 1935 by the Taos Pueblo artist Trinidad Archuleta. Directly south of the cabin is the meadow that was created when the trees were cleared. This is also where Mary and William McClure, the second owners of the ranch, grazed their angora goats at the turn of the 20th century.

When Lawrence, Frieda and Brett arrived they found the Homesteader’s Cabin and other ranch buildings in a sad state of disrepair. Lawrence, with the help of three Taos Pueblo Indians and a local carpenter, spent May and part of June 1924 repairing the buildings. The chimney of this cabin was rebuilt with adobe bricks and all the buildings were restored and reroofed. Lawrence even climbed over the tin roof on a hot day with a wet handkerchief over his mouth to clear out the rats’ nests. It was in this cabin that Lawrence worked on his manuscripts with typing duties shouldered by Lady Brett since Lawrence did not know how.

The Dorothy Brett Cabin

Sharon Oard Warner, Co-Chair of the Initiatives, in front of the Brett Cabin

Artist Dorothy Brett (1883-1977), better known as Brett or Lady Brett, studied painting at the Slade School in London from 1910-1916. During that time she established friendships with writers such as Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence and George Bernard Shaw, and painters Dora Carrington and Mark Gertler.

In January 1924, after his first trip to New Mexico, Lawrence asked several friends to move to Taos with him to create a utopian society he called “Rananim.” Only Brett accepted his offer. In March 1924, Lawrence, Frieda and Brett set sail for the United States. In May they arrived at the Kiowa Ranch with Lawrence and Frieda taking the larger cabin and Brett settling in the smaller one. Her days at the Kiowa Ranch were often spent painting. And while Brett had been deaf since childhood — she used an ear trumpet she called “Toby”– she would assist Lawrence by typing his manuscripts.

Lawrence left New Mexico in 1925, but Brett settled permanently in Taos, eventually becoming an American citizen. Known for her portraits, landscapes and depictions of American Indian scenes and ceremonials, Brett’s paintings are exhibited in London’s Tate Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery, the Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts in Scotland, and in fine art galleries in New Mexico. She died in 1977 at the age of 94.

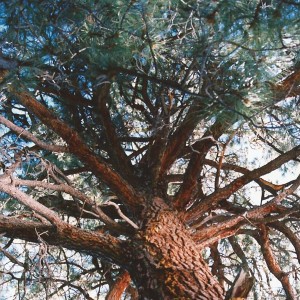

The Lawrence Tree

“The big pine tree in front of the house, standing still and unconcerned and alive…the overshadowing tree whose green top one never looks at…One goes out of the door and the tree-trunk is there, like a guardian angel. The tree-trunk, the long work table and the fence!” –D. H. Lawrence

Under this mammoth pine tree, D.H. Lawrence would spend his mornings writing at a small table. In 1929, five years after Lawrence’s final visit to New Mexico, artist Georgia O’Keeffe came to Taos. During her visit O’Keeffe spent several weeks at the Kiowa Ranch and painted the stately pine. O’Keeffe writes that she would lie on the long weathered carpenter’s bench under the tall tree staring up past the trunk, up into the branches and into the night sky. The scene is captured in her now famous oil painting, “The Lawrence Tree,” which is currently owned by the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, CT.

The Lawrence Memorial

After Lawrence died, Frieda returned to the ranch accompanied by Angelo Ravagli, her Italian lover and later third husband. In 1934, she had this memorial built for Lawrence. The following year Frieda had his body exhumed, cremated and the ashes brought to Taos. Her plan was to have the ashes housed in an urn in the memorial but Brett and Mabel Dodge Luhan wanted to scatter the ashes over the ranch (while Lawrence was alive the three women often competed for his attention). In response, Frieda dumped the ashes into a wheelbarrow containing wet cement and exclaimed, “now let’s see them steal this!” The cement was used to make the memorial’s altar. There are other stories concerning the whereabouts of Lawrence’s ashes but this one is the most widely accepted.

The simple, concrete altar displays Lawrence’s initials flanked by green leaves and yellow flowers. At the top of the altar is a statue of Lawrence’s personal symbol — the phoenix. Outside, to the left as one enters the memorial, is Frieda’s grave. She died in 1956 at her home in El Prado, NM on her 77th birthday. It was her wish that she be buried here. While visitors often refer to the building as a shrine, Frieda always insisted it be called the Lawrence Memorial.

Frieda Lawrence at home in the house she and Antonio Ravagli built at the D.H. Lawrence Ranch

Text by: Rachel Maurer

Senior Public Affairs Representative

UNM Public Affairs Dept